Handling the Holidays: Helping Grieving Children

Grief is an extremely difficult journey and can be even more challenging to navigate during the holidays. Despite the amount of time since a loss, the death of a family member, friend, pet, or even losses resulting from a parental divorce can be substantial triggers for children during the holidays. Grief does not have a timeline and will act, look, and feel differently from day to day, week to week, and year to year. When a family has experienced a loss, parents are struggling to manage their own grief in addition to supporting the children through theirs. Holidays are more difficult because they are a time when families are supposed to feel happy and joyful and instead, bereaved families feel sad and anxious. Grief and joyfulness are contradictions.

The following information is adapted from an article by Robin F. Goodman.

Retrieved from http://www.aboutourkids.org/articles/children_grief_what_they_know_how_they_feel_how_help

She states that we have come to expect certain reactions from children when dealing with death. Their fear, anger, sadness, and guilt are related to their:

- ability to understand the situation

- worry about others’ physical and emotional well-being

- desire to protect those who are living

- reactions to changes in home life

- changes in roles and expectations

- feelings of being different, alone, isolated

- sense of injustice

- concern about being taken care of and about the future

Children express their grief by their:

- behavior

- emotions

- physical reactions

- thoughts

There are some predictable ways that children understand and respond to death at different ages.

Infants and toddlers: Before age 3

The very young have little understanding of the cause or finality of death, as illustrated by a belief that leaves can be raked up and replaced on a tree. They are most likely to react to separation from a significant person and to the changes in their immediate world. Toddlers are curious about where things go and delight in disappearance and reappearance games such as “peek-a-boo.” Their distress at the changes in their environment following a death are displayed by:

- crying

- searching

- change in sleep and eating habits

Preschoolers and young children: 3-5 years old

With language and learning comes an interest in the world and children this age are full of questions, often repeated. They try to use newly acquired information. A 4-year-old on the plane for the first time looks out the window and asks “We’re in heaven — where are all the people?” They focus on the details of death and may also personalize the experience, perhaps by incorrectly perceiving the cause as stemming from them. For them, being dead can mean living under changed circumstances, so even though a child has seen someone buried underground there may be concern for the person getting hungry. At this age, death is equated with punishment. But it is also is seen as reversible; being dead means being still and being alive means moving. When playing cops and robbers, if someone is shot in “play,” merely standing up makes you alive once again. Children this age are apt to be sad, angry, scared or worried and communicate these feelings in their:

- tantrums, fighting

- crying

- clinging

- regression to earlier behaviors (such as nightmares, bedwetting, thumb-sucking)

- separation fears

- magical thinking that the person can reappear

- acting and talking as if the person is still alive

Early school age children: 6-9 years old

Children this age have the vocabulary and ability to comprehend simple concepts relating to germs and disease. There is still a fascination with concrete details as a way to organize information. When asked what happens when someone dies, a 6-year-old replied, “like a special car comes and it picks them up; a special sort of station wagon that has no back seat on it.” They have a sense of the importance of, and contributing factors to, personal health and safety. Yet their emotions and understanding can be incongruent. Therefore we see their less sophisticated beliefs such as in the power of their own thoughts to cause bad things to happen. They also personify death, thinking that a “boogey man” can snatch people away. They are most likely to display:

- anger

- denial

- irritability

- self-blame

- fluctuating moods

- withdrawal

- earlier behaviors

- school problems, such as avoidance, academic difficulty, lack of concentration

Middle school age children: 9-12 years old

By age 9 or 10, children have acquired a mature understanding of death. They know that: (1) it is a permanent state; (2) it cannot be reversed; (3) once you have died your body is no longer able to function; (4) it will happen to everyone at some time; (5) it will happen to them. This adult understanding can be accompanied by adult-like responses such as feeling a sense of responsibility, feeling different, being protective of others who have been affected, thinking certain emotions are childish or that they must put up a good front. The most common reactions are:

- crying

- aggression

- longing

- resentment

- isolation, withdrawal

- sleep disturbance

- suppressed emotions

- concern about physical health

- academic problems or decline

Families should be informed there is no right or wrong way to handle the holidays and anniversary times. The key to coping with grief is for each member to communicate needs and find the way that “feels” right for the family unit and to be flexible should needs change throughout the day. Some people find it helpful to be with family and friends, emphasizing the familiar. Others may wish to avoid old sights and sounds entirely and may take a trip to an exotic location. Others will find entirely new ways to acknowledge the season.

It is important to plan ahead, and also important to anticipate the changes they will need to make. It does take a little more effort to implement creative change in holiday planning. But flexibility is essential for the grieving family. Traditions bind families and societies tightly to one another. Altering our traditions to suit our current needs also makes sense. Each moment, each stage of life, demands its own customs and its own rituals.

The goal of the bereaved is to find a means of learning to live with the grief and sadness instead of being consumed by it. Allowing moments of sadness as well as laughter…especially during the holidays and anniversary periods.

Tips for parents to help grieving children during the holidays:

- Openly talk about memories involving the loved one during previous holiday seasons, but limit the loss from becoming the entire focus of the day.

- It is helpful to have an additional remembrance of the person who died. Light a candle in his or her honor. Hang an ornament on the tree that reminds each of the loved one. Encourage the children to draw a favorite memory to be displayed amidst decorations.

- If appropriate, engage in activities the children enjoyed doing with the person they lost.

- Remember, it is okay for parents to cry and show emotion in front of the children. They are looking to you to model both grief and healing. Moments of joy despite the grief.

- Lots and lots of family HUGS!!!!

Book Recommendations for parents and professionals:

Geranium Morning

by Sandy Powell

A little boy whose father dies in a car accident becomes friends with a little girl whose mom is dying of cancer. The girl’s mom dies before the book ends. It covers all kinds of feelings including the “if onlys”.

When Dinosaurs Die

by Laurie Krasny and Marc Brown

This book talks about different kinds of ways that people die and a little about mourning rituals, funeral, and different cultures.

A STORY FOR HIPPO

by Simon Putlock

This is for younger children about remembering someone by telling their stories.

Tear Soup

by Pat Schweibert, Chick DeKleyen and Taylor Bills

There are activities in the back of this book and questions you can ask for individuals, small groups or classroom guidance. There’s also a companion website http://www.griefwatch.com/tear-soup-home.html.

How it Feels When A Parent Dies

by Jill Krementz

It is a collection of stories written for children of all ages about their experience with the death of a parent.

Sad Isn’t Bad: A Good-Grief Guidebook for Kids Dealing with Loss (Elf-Help Books for Kids)

by Michaelene Mundy

Loaded with positive, life-affirming advice for coping with loss as a child, this guide tells children what they need to know after a loss–that the world is still safe; life is good; and hurting hearts do mend.

Creative Interventions for Bereaved Children

by Liana Lowenstein

A uniquely creative compilation of activities to help bereaved children express feelings of grief, diffuse traumatic reminders, address self-blame, commemorate the deceased, and learn coping strategies. Includes activities for children dealing with the suicide or murder of a loved one.

by Darah Curran, LCSW and Sheri Mitschelen, LCSW, RPT/S

Darah Curran is a Licensed Clinical Social Worker (LCSW) in the State of Virginia with 15 years experience working with children, adolescents and families. She has worked in home-based counseling and adolescent group homes. Darah has provided support for pediatric and adult individuals and families in outpatient and inpatient medical settings. She has presented in the community addressing the need for psychosocial support to patients and families navigating the medical system. She is currently employed at a non-profit agency providing short-term therapy to families affected by cancer and at Crossroads Family Counseling Center, LLC.

Sheri Mitschelen, Owner and Director of Crossroads Family Counseling Center, LLC in Fairfax, VA is a Licensed Clinical Social Worker (LCSW) in the State of Virginia and a Registered Play Therapy-Supervisor (RPT-S). Along with her therapy and supervision practice, she is a member of the adjunct faculty at the National Catholic University School of Social Service and George Mason University in the School of Social Work. She is also the Co-owner and Executive Director of Family and Play Institute of Virginia, a play therapy training program.

The Magical Healing Power of FAIRY HOUSES

By Meredith Reed

The healing power of nature spans across several aspects of well-being, including mental, physical, and emotional health. The benefits of time spent in nature for children are powerful as it helps to shape overall development and foster stewardship and protection of the environment. A creative way of encouraging children to go outside is with the activity of building fairy houses. The simple challenge of creating a fairy house encourages children to get outside, respect nature, explore their surroundings, and expand their imaginations.

Fairy houses can be created using sticks, stones, pebbles, branches, leaves, seaweed, pine cones, nuts, shells, feathers, and any other natural materials. It is important to stress that respect should be given to plants still living and growing and should not be disturbed. The houses can be built in special places, away from roads and busy pathways, perhaps at the base of a tree. Different locations and different seasons will yield unique looking fairy houses. Once the fairy house is built, children will enjoy watching it welcome surprise visitors, or “fairies,” like toads, ants, and birds.

Building fairy houses gives children a chance to step away from the world of technology, computer screens, televisions and cell phones. A daily dose of green time will improve attention, focus and memory. Nature also has a healing power, improving children’s cognitive development. Creative play in nature nurtures language and collaborative skills, awareness, reasoning and observational skills. Physical health is improved and boosts the immune system.

Nature also buffers the impact of life stress on children, suggesting that building fairy houses can be a resource for children dealing with everything from everyday stress to trauma. Spending time in nature helps to instill a sense of peace and connectivity through observation and creativity. The task of building a fairy house fosters autonomy, concentration, and self-discipline, which eve helps to improve test scores. Building fairy houses with others promotes healthier interpersonal relationships. Research has shown that children who play together in nature have more positive feelings about each other. Playing in nature may even reduce bullying, suggesting that fairy houses can act as a healthy activity for children to engage in alone or with family and friends.

How can YOU use fairy houses in your work with children?

- Consider creating fairy houses to help children cope with loss, such as the loss of a grandparent, friend, or other family member. Fairy houses can represent a special place for them to remember and connect with the memories of their loved one.

- Consider using fairy houses with kids who are transitioning to a new home. It is natural for kids to long for their old home, old school, or old friends. A fairy house can be a creative way to remember various aspects of what they loved.

- Consider creating fairy houses for children who are experiencing stress or turmoil. It is common for us to ask kids to imagine a safe or special place. Now add a layer… let’s create one!

What other ways can YOU imagine using fairy houses?

Learn more at:

http://childrenandnature.ning.com/video/building-fairy-houses-with-marghanita-hughes

by Suzanne Getz Gregg, PhD, LPC, RPT/S, Virginia Beach

As play therapists, we are well-trained to invite, facilitate, and respond to the child’s symbolic representation of personal experience through play. We are well-versed in methods designed to help understand and decode the processes of exploration and mastery via meaningful play themes. But where do we turn when the child, regardless of age, reverts to infantile dysregulation and cannot employ the play-based items we offer? Fortunately for us, Phyllis Booth has been teaching and training in Theraplay techniques for several decades now. On Friday, January 18th, we warmly welcomed her back to the winter seminar series of the Virginia Association for Play Therapy. Her skills in entering into and modifying the young child’s stance across sensory and motor channels are paramount.

The earlier the developmental wound or challenge, the less verbally-mediated it is. When harsh early experiences result in mistrust, shame, and insecurity, the child develops a view of self-world-other that is negative and disorganized. Without effectively soothing interactions, he or she becomes easily dysregulated. It follows, then, that corrective developmental experiences should be primarily body-based in origin to best effect change. By giving dozens of demonstrations, Phyllis showed how learning, or relearning, the foundations of healthy relatedness results in self-regulation, secure attachment, and self-worth. Parents typically serve as the agents of change, with therapists advising and coaching them in the process. For a child to learn to relax and let trustworthy others take charge, parents need to be directive. This stands in contrast to our traditional methods of non-directive play therapy, which are more suitable at older ages.

At root, then, is the core dilemma of how to direct a child who disengages and refuses to participate, or over-reaches in attempts to over-control the interaction. Both are avoidance tactics, meant to evade the elemental give-and-take of dyadic relationships. Priceless video clips captured the essence of Phyllis’s delightfully playful and attuned style. By voice, by touch, by smile, she demonstrated how to draw a child in by exclaiming over the wonder of who they are. As parents explore how to address the essence rather than the behavior of a child, they help promote recovery from the deep wounds of feeling unwanted, unsafe, unloved.

We learned how tug-of-war naturally reengages the child’s push-pull in a dyad without triggering protest. How a shake of powder in the hand lets an adult trace the lines in a child’s palm in an effort to reestablish safe touch. How using the child’s feet to cover our eyes in a game of peek-a-boo lets the child recline without an awareness of giving in. How the joy of pushing over an adult is linked with pulling them back up, making the relationship bidirectional, as is desired. How an adult leading a rousing rendition of Row Your Boat can vary the rhythm, thus by default the child learns to conform and gradually rewires a patterned sense of regulation. Though the child is unaware of being led, through these and dozens of other exercises, his or her relief in letting go into the joy of true connection is sweetly apparent at every turn. Thank you, Phyllis, for lighting the way for us to follow, on behalf of all the children we serve!

How Parents and Play Therapists can Help Children with Transitions by Identifying Sensory Processing Disorder

By Sheri Mitschelen, LCSW, RPT/S

VAPT Northern Virginia Chapter Chair

This time of year comes with lots of transitions with Daylight Savings time, the weather changing and Spring break from school. While it’s typical for children to have trouble with transitions, some children and adults have more trouble than others. These children may have anxiety which makes it more difficult to transition and/or they may have Sensory Issues or Sensory Processing Disorder which makes it troublesome. Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD, formerly known as sensory integration dysfunction) is a condition that exists when sensory signals don’t get organized into appropriate responses. Pioneering occupational therapist and neuroscientist, A. Jean Ayres, PhD, likened SPD to a neurological “traffic jam” that prevents certain parts of the brain from receiving the information needed to interpret sensory information correctly. A person with SPD finds it difficult to process and act upon information received through the senses, which creates challenges in performing everyday tasks. Motor clumsiness, behavioral problems, anxiety, depression, school failure, and other impacts may result if the disorder is not treated effectively.

Ahn, Miller, Milberger, McIntosh, 2004 estimate that at least 1 in 20 children’s daily lives is affected by SPD. Another research study by the Sensory Processing Disorder Scientific Work Group (Ben-Sasson, Carter, Briggs-Gowen, 2009) suggests that 1 in every 6 children experiences sensory symptoms that may be significant enough to affect aspects of everyday life functions. Symptoms of Sensory Processing Disorder, like those of most disorders, occur within a broad spectrum of severity. While most of us have occasional difficulties processing sensory information, for children and adults with SPD, these difficulties are chronic, and they disrupt everyday life.

According to the SPD Foundation, children with Sensory Processing Disorder often have problems with motor skills and other abilities needed for school success and childhood accomplishments. As a result, they often become socially isolated and suffer from low self-esteem and other social/emotional issues. These difficulties put children with SPD at high risk for many emotional, social, and educational problems, including the inability to make friends or be a part of a group, poor self-concept, academic failure, and being labeled clumsy, uncooperative, belligerent, disruptive, or “out of control.” Anxiety, depression, aggression, or other behavior problems can follow. Parents may be blamed for their children’s behavior by people who are unaware of the child’s challenges.

Effective treatment for Sensory Processing Disorder is available, but far too many children with sensory symptoms are misdiagnosed and not properly treated. Untreated SPD that persists into adulthood can affect an individual’s ability to succeed in marriage, work, and social environments.

Common Signs of Sensory Processing Problems

From http://sensorysmarts.com/signs_of_spd.html

Out-of-proportion reactions to touch, sounds, sights, movement, tastes, or smells, including:

- Bothered by clothing fabrics, labels, tags, etc.

- Distressed by light touch or unexpected touch

- Dislikes getting messy

- Resists grooming activities

- Very sensitive to sounds (volume or frequency)

- Squints, blinks, or rubs eyes frequently

- Bothered by lights or patterns

- High activity level or very sedentary

- Unusually high or low pain threshold

Motor skill and body awareness difficulties, including:

- Fine motor delays (e.g., crayons, buttons/snaps, beading, scissors)

- Gross motor delays (e.g., walking, running, climbing stairs, catching a ball )

- Illegible handwriting

- Moves awkwardly or seems clumsy

- Low or high muscle tone

Oral motor and feeding problems, including:

- Oral hypersensitivity

- Frequent drooling or gagging

- “Picky eating”

- Speech and language delays

Poor attention and focus: often “tunes out” or “acts up”

Uncomfortable/easily overstimulated in group settings

Difficulty with self-confidence and independence

Many such behaviors are typical at certain stages of development. Many toddlers dislike fingerpaints. But a 10-year-old who has a meltdown during every art project is a different story. A strong dislike of itchy fabric or brushing teeth, shyness with strangers, or fear of a noisy goat at the petting zoo can be “typical” for a younger child as long as these sensory experiences do not interfere with day-to-day function. A child with sensory issues has responses to such experiences that are way out of proportion, consistently showing behaviors that can’t be dismissed.

Sensory Smart Tip: Make transitions easier for the child with sensory processing disorder, or SPD, by providing a clear picture of what comes next.

In Raising a Sensory Smart Child The Definitive Handbook for helping your Child With Sensory Processing Issues, Lindsey Biel, OTR/L and Nancy Peske note that for children with sensory processing issues transitions from one activity to another that other children handle easily can seem abrupt and unpleasant. What seems to us to be a fun shift in activities may be, to them, like slamming on the brakes and or making a sharp turn that causes them to feel disoriented. To transition a child, first, get her attention. Call her name and tell her that you’re going to switch activities soon, and give her a time frame for completing the switch. For an older child, it may be stating something like “in fifteen minutes you need to do your homework…” For a younger child, it may be “when you’ve gone down the slide three more times, we’re leaving the park.” Keep your voice inviting but warm and firm.

Carol Kranowitz, M.A. has authored The Out of Sync Child and The Out of Sync Child Has Fun which gives lots of play activities regarding the various senses that are fun and safe to help with improving Sensory Processing Disorder. This is a great book for parents and Play therapist to use when working with SPD children.

To learn more about Sensory Processing Disorder go to http://www.spdfoundation.net/about-sensory-processing-disorder.html and to find an Occupational Therapist who can assess children for SPD go to http://www.aota.org/.

The Role of Play Therapists Addressing the Needs of Children in Foster Care: Treatment and Advocacy

Virginia’s statistics for children in foster care for August 2012 indicate that a little over 5,000 children are currently in foster care with almost half the children placed between the ages of 13 – 18 years of age (2,273 adolescents). The major reasons for removal from the home were sited as neglect (51.31%) and Child Behavior Problem (21.16%). Parent’s drug abuse (16.72%), physical abuse (15.29%) and inadequate housing (14.22%) were the other highest reasons for removing a child from their home. The majority of children were reunified with their parents (35.36%), adopted (24.81) or placed in long-term foster care (12.44%). These statistics indicate that the experiences of these children are severe and only about a third of children are returned to their homes.

Children removed from their homes are at-risk of experiencing significant attachment problems that compound their trauma issues. This is a vulnerable population that has complex issues and treatment needs often not understood by the professionals and families caring for them. The social welfare system of professional making decisions about the care and planning for these children are often unaware of the clinical issues associated with trauma and attachment. Foster parents are often ill equipped to manage the behavioral manifestations of trauma and attachment symptoms. In Virginia, the majority of children experience more than one foster care placement, which is evidence of the trauma and attachment problems experienced by these children and the lack of understanding by caregivers of these issues. To further compound the problem facing these children, very few mental health providers are trained to provide the kind of specialized care needed by these children and their caregivers. The result is that our most vulnerable population of children are not getting the appropriate services needed to change the long-term negative impact of trauma and attachment problems.

Play therapy professionals are in the specific role of providing treatment to children and adolescents with a special emphasis on ensuring that the services providers meet the unique social, emotional, cognitive, and physical needs for this population. As play therapists, we understand the benefits of play and expressive arts when working with children and adolescents. The Virginia Association for Play Therapy has led the charge in Virginia to help play therapists develop trauma-informed play therapy skills with an emphasis on attachment by partnering with the Mary Ainsworth Clinic at the University of Virginia to teach the Circle of Security Model, National Institute for Trauma and Loss in Children and the Child Trauma Academy to understand the neurobiology of trauma and attachment.

How can play therapist help make a difference? Help educate parents, caregivers and social welfare professionals about the impact of trauma and attachment for this population. The federal Administration for Children and Families has recognized the need to integrate trauma-informed systems of care at the state and local child welfare agency levels. Now is the time to advocate for the needs of these children and increase awareness of using play therapy to heal the wounds of trauma. Educate your self about effective models of treatment for this population that are trauma-informed and attachment based to increase awareness of the need to improve the quality of services provided to these children.

By Cathi Spooner

Addressing Back to School Jitters

As the new school year begins many children and teens will have butterflies in their stomachs and some may demonstrate an increase in irritability or exhibit behavioral concerns. For some kids there are meltdowns associated with the anxiety of a new school year. Here are some tips on how we can help families feel better prepared & ease these jitters:

As the new school year begins many children and teens will have butterflies in their stomachs and some may demonstrate an increase in irritability or exhibit behavioral concerns. For some kids there are meltdowns associated with the anxiety of a new school year. Here are some tips on how we can help families feel better prepared & ease these jitters:

• BE PREPARED

Help your child become familiar with the bus-stop, bus route, school building, and schedule. If the school offers an orientation, encourage them to attend and be present to answer questions afterward. The week & night before choose the first day outfit, pack lunch or gather lunch money, help them pack their book-bag with the needed supplies, etc. These tangible preparations can help kids feel ready and get a good night sleep before the first day!

• ENGAGE IN CONVERSATION ABOUT SCHOOL

Talk with your kids about who their new teachers are, making sure to emphasize the positive. Also, be there to listen to disappointments to not having friends in their class, and don’t forget to help them feel confident to meet new friends. Set aside time in the evening after each day of school to learn about their day. Some academic and social question prompts are:

Who did you meet today?

What subject did you like the most?

What do your friends like to do?

Who do you eat lunch with?

Are there classmates that they don’t get along with?

Making this conversation a part of the daily routine will help your child feel they can come to you with both the good and the bad. It will help them to find solutions to their problems with and without you. One of my favorite childhood memories is a very busy mother taking the time to sit with me each afternoon with a cup of tea or snack and talk about the day.

• SET A ROUTINE (EVEN BEFORE DAY 1)

It is easy with the long days of summer to slip into late dinners and even later bedtimes. While that is part of the joy of summer, it is important to begin getting into the school routine a few weeks before school starts. Begin going to bed earlier each night with healthy bedtime hygiene. Help your child begin waking up to an alarm close to the time they will have to get up for school. Decide when during the school year activities of daily living will take place and begin to implement that schedule (i.e. shower the evening before, set out clothes, etc). This will make the night before and the first day of school smoother for both you and your child! It will also help with getting a good night’s rest, which will all know is important.

• TURN OFF TECHNOLOGY & TUNE IN TO EACH OTHER

Spending quality time (related to academics and to fun) will help your child feel supported and that you are engaged not only with their learning, but in their lives. This doesn’t necessarily require a lot of time (15 minutes here and there adds up), but it does require complete attention and disconnection from distracting technology (blackberries & ipads count). While these can be wonderful communication tools, the purpose of this time is for you and your child to connect on the most basic, human level, which is face to face. Talk with your children about what they are learning (in and out of school), become interested in their passions, tell them what you see and love about the world around you. LISTEN to your child’s experience and delight in learning together. This will have a positive impact on their social-emotional development in addition to fostering their academic interest.

*Some information gathered from:

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/craig-a-mertler/backtoschool-preparations_b_1734951.html http://suite101.com/article/calming-back-to-school-nerves-a63862

* A good article with tips directed to youth: http://wvgazette.com/Entertainment/FlipSide/201108170968

By Katie Masey

VAPT Chapter Chair

Rockbridge Area

Neuroscience in the PlayRoom – Why It Matters

Thanks to APT playmate, Cherie L. Spehar, LCSW, CTS, CTC, for contributing this informative blog about neuroscience and our work in the play therapy room. Cherie is a Play Therapist, Certified Trauma Specialist and CT Consultant and, my valued colleague and friend.

I hope you enjoy her thoughts and get yourself and some playmates signed up to attend the VAPT workshop, Becoming a Brain-Wise Therapist: Using Play Therapy and Expressive Arts Across the Lifespan, to be held June 18 and , 2012, in Harrisonburg, VA. See more information and register at http://vapt.cisat.jmu.edu/

CE’s (12!!) are offered from APT, APA, NBCC and NASW. We have participants coming from Maine, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, North Carolina, West Virginia and Virginia! Do not miss this very affordable opportunity to learn and play with Bonnie Badenoch, author of Becoming a Brain-Wise Therapist and also to shop again with the Self Esteem Shop, right on-site!

Playfully,

Anne Stewart, VAPT President

Take it away, Cherie…

If you are a play therapist, I am certain that by now you have been hearing about the ongoing practice points related to neuroscience and psychotherapy. As well, there is much activity in the field about how this specifically applies to Play Therapy. Isn’t it exciting to see the brain-based research to support what we have seen in our play therapy rooms for so many years?

Sometimes, though, teasing out the most relevant practice points can be daunting. Here you will find a brief synthesis of the most important ways that the integration of neuroscience and play therapy can aid your practice and ultimately the growth and resilience of the young ones in your care.

First, one of the most important aspects of understanding the neuroscience of play is that it will directly enhance your understanding of trauma. We are now aware of how the brain and body respond to emotionally overwhelming events. Trauma creates neural pathways that keep the brain in a constant state of hyperarousal. The neuroscience of play based interventions directly works to counteract a revved up nervous system and supports the development of healthy, meaningful, and long-lasting coping responses.

Another overarching benefit to bringing brain science into your play room is that we now have concrete information to support our therapeutic process. This is particularly important for engaging parents and caregivers. For example, I can teach them that, because play is not only the child’s language, but the brain’s language, that their child is forming vital neural connections that strengthen his resilience. I can share that play therapy is a way of untangling brain pathways that are causing their child distress, and that it directly helps the creation of healthy new connections.

Aside from the umbrella of these practice points, here is another list I share with my play therapist supervisees:

• It informs our practice in an entirely unique way. Just by observing the characteristics of play, we can better assess which part of the child’s brain is at work when distressing symptoms are present.

• By understanding the brain science of play, and a child’s brain development in general, we can provide accurate and spot on practices and suggestions for parents to use at home.

• By providing psychoeducational guidance on the neuroscience behind play based interventions, we can build credibility with parents and families for the work we are doing and the results they can expect to see.

• We can help the child choose appropriate sensory regulators that will maximize his relief in between sessions.

• Play has the inherent component of honoring private logic while simultaneously helping create a new trauma narrative.

• Repetitive body conditioning happens during play – which is exactly what is needed for self-regulation.

Play is an essential component of our existence. This is true for adults and children alike. The neuroscience of trauma and play fits well with all play therapy approaches and is not only respectful of the various processes, but it enhances them.

May your own learning be enhanced and nurtured as you “grow brain” and play it out!

Hello world!

Welcome to our new Virginia Association for Play Therapy blog!

The VAPTPLAY blog will appear two times a month and feature contributions from our chapter chairs, members, and guests. Let me know if you are interested in authoring a 300 to 500 word topical post.

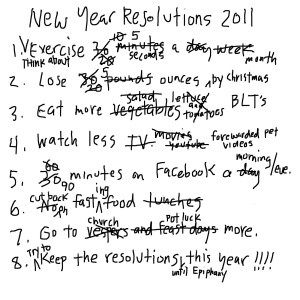

Many of us have composed resolutions to begin 2012. Our resolutions may have been boldly announced to family and friends or just thoughtfully considered in the form of a private “note to self.” Popular resolutions are to spend more time with family and friends, lose weight, get better organized, and learn something new. While resolutions tend to have a bad reputation they have hopeful, aspirational qualities and are simply goals we have for ourselves. Resolutions are more successful when they are SMART, viz., meaning that they are Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Rewarding, and Time-limited. So instead of saying, “I resolve to have more play in my life,” you might state “I will dance in my living room to 3 fun and inspirational songs every Sunday and Wednesday” or “I will skip to my car in the morning” or “I will subscribe to Writer’s Almanac list serve” or “I will have tea with ____ the first Friday of each month.”

Or, this seasonal favorite, “I will attend the VAPT Winter Workshop to learn and play with my VAPT friends and colleagues!”

(Go to http://vapt.cisat.jmu.edu/winterconference12/ and accomplish the registration for this great resolution right now!)

Resolutions are more  likely to be accomplished when they are stated positively and emphasize what you will gain or add, rather than focused on what you will stop, quit, or lose. Sharing your goals with people that will offer encouragement and support to help you stay the course adds to the equation for success.

likely to be accomplished when they are stated positively and emphasize what you will gain or add, rather than focused on what you will stop, quit, or lose. Sharing your goals with people that will offer encouragement and support to help you stay the course adds to the equation for success.

Of course, resolutions can always be amended, as the picture of New Year’s Resolutions for 2011 shows!

What are your playful resolutions for 2012?

![mother_comforting_young_son[1]](https://vaptplay.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/mother_comforting_young_son1.jpg?w=300&h=204)